… or at least that’s what it SHOULD stand for. Why? Well, besides the fact that optimization is only one of two advanced sourcing & procurement technologies that have proven to deliver year-over-year cost avoidance (“savings”) of 10% or more (which becomes critical in an inflationary economy because while there are no more savings, negating the need for a 10% increase still allows your organization to maintain costs and outperform your competitors), it’s the only technology that can meet today’s sourcing needs!

COVID finally proved what the doctor and a select few other leading analysts and visionaries have been telling you for over a decade — that your supply chain was overextended and fraught with unnecessary risk and cost (and carbon), and that you needed to start near-sourcing/home-sourcing as soon as possible in order to mitigate risk. Plus, it’s also extremely difficult to comply with human rights acts (which mandate no forced or slave labour in the supply chain), such as the UK Modern Slavery Act, California Supply Chains Act, and the German Supply Chain Act if your supply chain is spread globally and has too many (unnecessary) tiers. (And, to top it off, now you have to track and manage your scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon in a supply chain you can barely manage.)

And, guess what, you can’t solve these problems just with:

- supplier onboarding tools — you can’t just say “no China suppliers” when you’ve never used suppliers outside of China, the suppliers you have vetted can’t be counted on to deliver 100% of the inventory you need, or they are all clustered in the same province/state in one country

- third party risk management — and just eliminate any supplier which has a risk score above a threshold, because sometimes that will eliminate all, or all but one, supplier

- third party carbon calculators — because they are usually based on third party carbon emission data provided by research institutions that simply produce averages for a region / category of products (and might over estimate or under estimate the carbon produced by the entire supply base)

- or even all three … because you will have to migrate out of China slowly, accept some risk, and work on reducing carbon over time

You can only solve these problems if you can balance all forms of risk vs cost vs carbon. And there’s only one tool that can do this. Strategic Sourcing Decision Optimization (SSDO), and when it comes to this, Coupa has the most powerful platform. Built on TESS 6 — Trade Extensions Strategic Sourcing — that Coupa acquired in 2017, the Coupa Sourcing Optimization (CSO) platform is one of the few platforms in the world that can do this. Plus, it can be pre-configured out-of-the-box for your sourcing professionals with all of the required capabilities and data already integrated*. And it may be alone from this perspective (as the other leading optimization solutions are either integrated with smaller platforms or platforms with less partners). (*The purchase of additional services from Coupa or Partners may be required.)

So why is it one of the few platforms that can do this? We’ll get to that, but first we have to cover what the platform does, and more specifically, what’s new since our last major coverage in 2016 on SI (and in 2018 and 2019 on Spend Matters, where the doctor was part of the entire SM Analyst team that created the 3-part in-depth Coupa review, but, as previously noted, the site migration dropped co-authors for many articles).

As per previous articles over the past fifteen years, you already know that:

- it’s an optimization-based negotiation platform for RFX & Auctions (2008)

- it’s easy to use with OLAP reporting and integrated data classification (2009)

- regardless of if you’re public or private, it generates fantastic results (2010)

- it also offers constraint templates by category and true ROLAP (not just OLAP) (2010)

- industry first fact sheets for optimization data definition of any kind of data (2011)

- one of the first examples of response dependent RFIs / data collection in a modern sourcing platform (2011)

- powerful optimization-backed e-Auctions (i.e. real time optimization) (2013)

- extended scenario definitions, a plethora of constraint categories, and advanced feedback mechanisms (2013)

- auto-formula extraction from enhanced fact sheets, a formula analyzer, and enhanced visualizations (2013)

- a UI with a focus on UX and composable workflows long before “configurable workflows” and “orchestration” became the big thing (2016)

- an analytics rule language that supports the construction of advanced formulas and rules for optimization using an advanced formula language (2016)

- automated reasoning and guided rule construction engine (2016)

- integrated support for complexity; powerful analytics to be used in sourcing as well as powerful optimization (2018; Spend Matters)

- buyer centricity and integrated risk data (2018; Spend Matters)

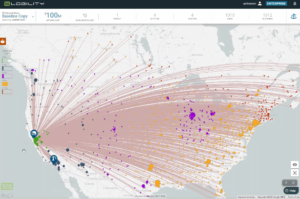

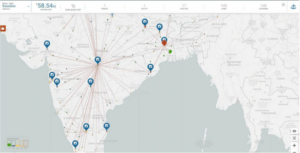

- extremely competitive as its capable of analyzing global billion dollar spend categories in a single scenario with hundreds of item requirements, thousands of potential products, thousands of suppliers and carriers and tens of thousands of lanes (2018: Spend Matters)

- with industry leading connectivity & analytics encapsulation (2019: Spend Matters)

So now all we have to focus on are the recent improvements around:

- “smart scenarios” that can be templated and cross-linked from integrated scenario-aware help-guides

- “Plain English” constraint creation (that allows average buyers & executives to create advanced scenarios)

- fact-sheet auto-generation from spreadsheets, API calls, and other third-party data sources;

including data identification, formula derivation and auto-validation pre-import - bid insights

- risk-aware functionality

“Smart Events”

Optimization events can be created from event templates that can themselves be created from completed events. A template can be populated with as little, or as much as the user wants … all the way from simply defining an RFX Survey, factsheet, and a baseline scenario to a complete copy of the event with “last bid” pricing and definitions of every single scenario created by the buyer. Also, templates can be edited at any time and can define specific baseline pricing, last price paid by procurement, last price in a pre-defined fact-sheet that can sit above the event, and so on. Fixed supplier lists, all qualified suppliers that supply a product, all qualified suppliers in an area, no suppliers (and the user pulls from recommended) and so on. In addition to predefining a suite of scenarios that can be run once all the data is populated, the buyer can also define a suite of default reports to be run, and even emailed out, upon scenario completion. This is in addition to workflow automation that can step the buyer through the RFX, auto-respond to suppliers when responses are incomplete or not acceptable, spreadsheets or documents uploaded with hacked/cracked security, and so on. The Coupa philosophy is that optimization-backed events should be as easy as any other event in the system, and the system can be configured so they literally are.

Also, as indicated above, the help guides are smart. When you select a help article on how to do something, it takes you to the right place on the right screen while keeping you in the event. Some products have help guides that are pretty dumb and just take you to the main screen, not to the right field on the right sub-screen, if they even link into the product at all!

“Plain English” Constraint Creation

Even though the vast majority of constraints, mathematically, fall into three/four primary categories — capacity/allocation, risk mitigation, and qualitative — that isn’t obvious to the average buyer without an optimization, analytical, or mathematical background. So Coupa has spent a lot of time working with buyers asking them what they want, listening to their answers and the terminology they use, and created over 100 “plain english” constraint templates that break down into 10 primary categories (allocation, costs, discount, incumbent, numeric limitations, post-processing, redefinition, reject, scenario reference, and collection sheets) as well as a subset of most commonly used constraints gathered into a a “common constraints” collection. For example, the Allocation Category allows for definition “by selection sheet”, “volume”, “alternative cost”, “bid priority”, “fixed divisions”, “favoured/penalized bids”, “incumbent allocations maintained”, etc. Then, when a buyer selects a constraint type, such as “divide allocations”, it will be asked to define the method (%, fixed amount), the division by (supplier, group, geography), and any other conditions (low risk suppliers if by geography). The definition forms are also smart and respond to each, sequential, choice appropriately.

Fantastic Fact Sheets

Fact Sheets can be auto-generated from uploaded spreadsheets (as their platform will automatically detect the data elements (columns), types (text, math, fixed response set, calculation), mappings to internal system / RFX elements), and records — as well as detecting when rows / values are invalid and allow the user to determine what to do when invalid rows/values are detected. Also, if the match is not high certainty, the fact-sheet processor will indicate the user needs to manually define and the user can, of course, override all of the default mappings — and even choose to load only part of the data. These spreadsheets can live in an event or live above the event and be used by multiple events (so that company defined currency conversions, freight quotes for the month, standard warehouse costs, etc. can be used across events).

But even better, Fact Sheets can be configured to automatically pull data in from other modules in the Coupa suite and from APIs the customer has access to, which will pull in up to date information every time they are instantiated.

Bid Insights

Coupa is a big company with a lot of customers and a lot of data. A LOT of data! Not only in terms of prices its customers are paying in their procurement of products and services, but in terms of what suppliers are bidding. This provides huge insight into current marketing pricing in commonly sourced categories, including, and especially, Freight! Starting with freight, Coupa is rolling out a new bid pricing insights for freight where a user can select the source, the destination, the type (frozen/wet/dry/etc), and size (e.g. for ocean freight, the source and destination country, which defaults to container, and the container size/type combo and get the quote range over the past month/quarter/year).

Risk Aware Functionality

The Coupa approach to risk is that you should be risk-aware (to the extent the platform can make you risk aware) with every step you take, so risk data is available across the platform — and all of that risk data can be integrated into an optimization project and scenarios to reject, limit, or balance any risk of interest in the award recommendations.

And when you combine the new capabilities for

- “smart” events

- API-enabled fact sheets

- risk-aware functionality

that’s how Coupa is the first platform that literally can, with some configuration and API integration, allow you to balance third party risk, carbon, and cost simultaneously in your sourcing events — which is where you HAVE to mange risk, carbon, and cost if you want to have any impact at all on your indirect risk, carbon, and cost.

It’s not just 80% of cost that is locked in during design, it’s 80% of risk and carbon as well! And in indirect, you can’t do much about that. You can only do something about the next 20% of cost, risk and carbon that is locked in when you cut the contract. (And then, if you’re sourcing direct, before you finalize a design, you can run some optimization scenarios across design alternatives to gauge relative cost, carbon, and risk, and then select the best design for future sourcing.) So by allowing you to bring in all of the relevant data, you can finally get a grip on the risk and carbon associated with a potential award and balance appropriately.

In other words, this is the year for Optimization to take center stage in Coupa, and power the entire Source-to-Contract process. No other solution can balance these competing objectives. Thus, after 25 years, the time for sourcing optimization, which is still the best kept secret (and most powerful technology in S2P), has finally come! (And, it just might be the reason that more users in an organization adopt Coupa.)